Reading Time: 5 minutes

The Jetpack Navigation component is a very welcome add-on that makes the development of Android apps so much easier. No more committing Fragment transactions, and no more hassle to make sure that the up- and back button give the user the expected experience, not to mention the trouble of having to maintain a concise back stack for deep links and finally: How did we survive for so long without that visual navigation graph?

Google offers an excellent code lab to get to know navigation and to play with it so there is no need to expand on that, although in the Android developer guide for the Navigation component, the term ‘form factor’ is mentioned that’s about it. Google doesn’t tell us what navigation has to offer in that respect. In this article, I’ll discuss the single activity aspect of the Jetpack navigation in combination with the use of ViewModels, and the positive side effect that this ‘golden combination’ can have on implementing different navigation flows for various form factors.

The promise of Fragments

Fragments were first introduced in Android 3.0 HoneyComb (API level 11). An important promise of Fragments was that tablets apps wouldn’t just look like blown-up phone apps, but we could re-use and combine UI elements of phone apps on tablets. Unfortunately this promise was never fulfilled, the practical implementation was cumbersome and a cause for headaches among developers.

What changed with the introduction of Jetpack Navigation?

So, Fragments didn’t really live up to that promise, but what does Jetpack Navigation change to all that? Well, its the combination of Jetpack Navigation and the Model-View-ViewModel (short: MVVM) architectural pattern, that potentially can cure developers from their headaches.

The MVVM architecture is part of the Architecture Components, which also belongs to Android’s Jetpack. The lifecycle of every ViewModel is related to its lifecycle owner, and its state will survive the configuration changes of that owner. So if that owner is the ‘single’ Activity that controls the navigation flow, then the ViewModels could function as the glue between the different Fragments that are part of the navigation flow, whether the fragments are placed next to each other on the screen of a tablet or whether they are placed sequentially, one after the other, in the flow of a smaller phone.

How to approach this?

Imagine that we are asked to make a simple app that navigates on a phone from a screen with a number-picker and a button that reads ‘Next’ to a second screen that displays the square root of that previously selected number. On a tablet this app should show the number-picker and the square root of the selected number besides each other on the same screen.

First, determine the breakpoints that differentiate your phone app from your tablet app. For example, let’s say, we want to differentiate where the smallest width (the shortest side) is 600dp. So we define that we’re dealing with a tablet when the shortest side of the device is 600dp or larger.

Then we create a navigation file for both sides of that breaking point:

- for phones: main/res/navigation/mobile_navigation.xml

- for tablets: main/res/navigation-sw600dp/mobile_navigation.xml

Next, define a fragment for every re-usable UI element:

- one for the numberpicker -> NumberpickerFragment

- one for displaying the square root of the selected number -> SquareRootFragment

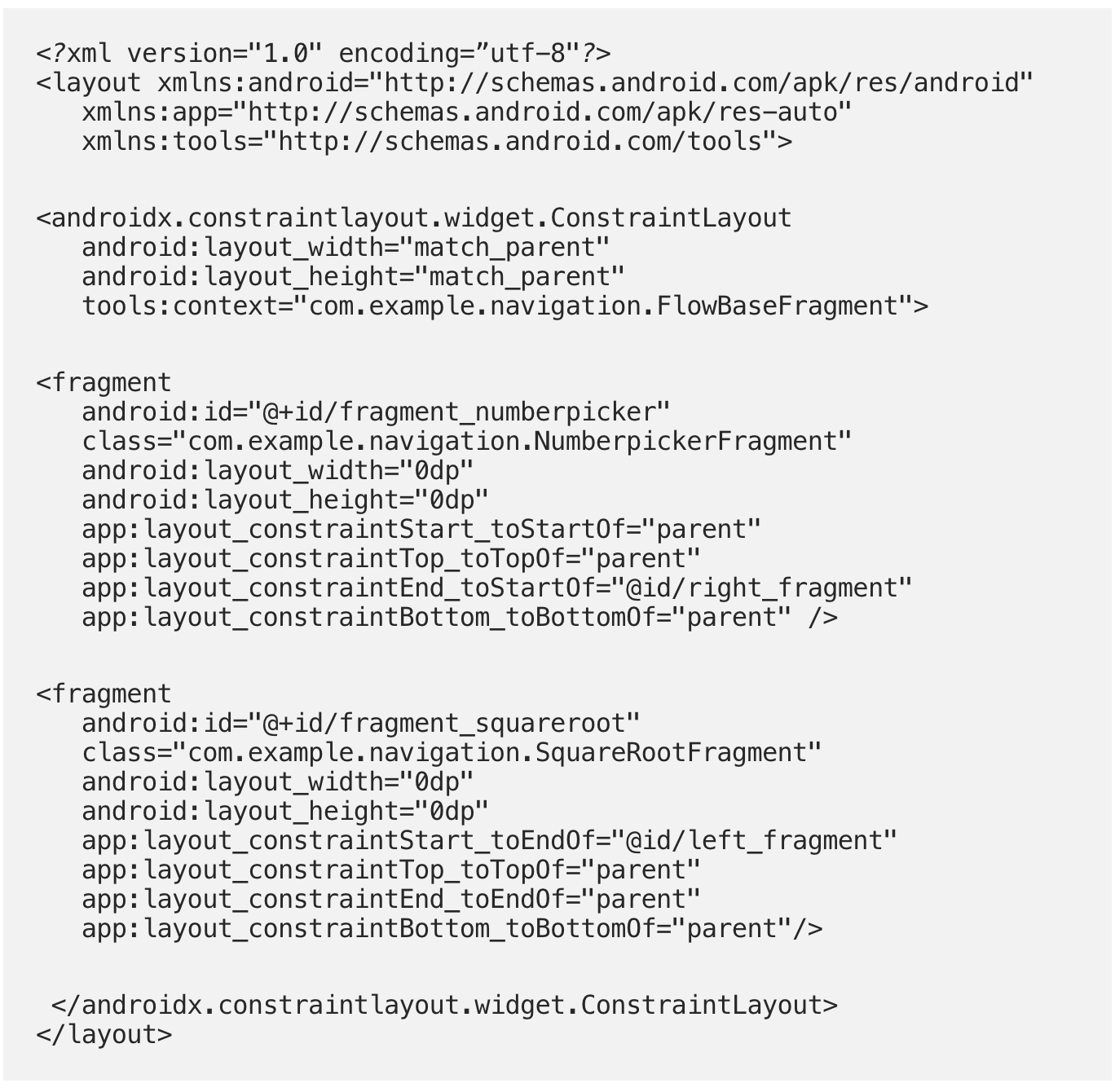

For the Tablet:

Next, for the tablet, aggregate these fragment as sub-fragments:

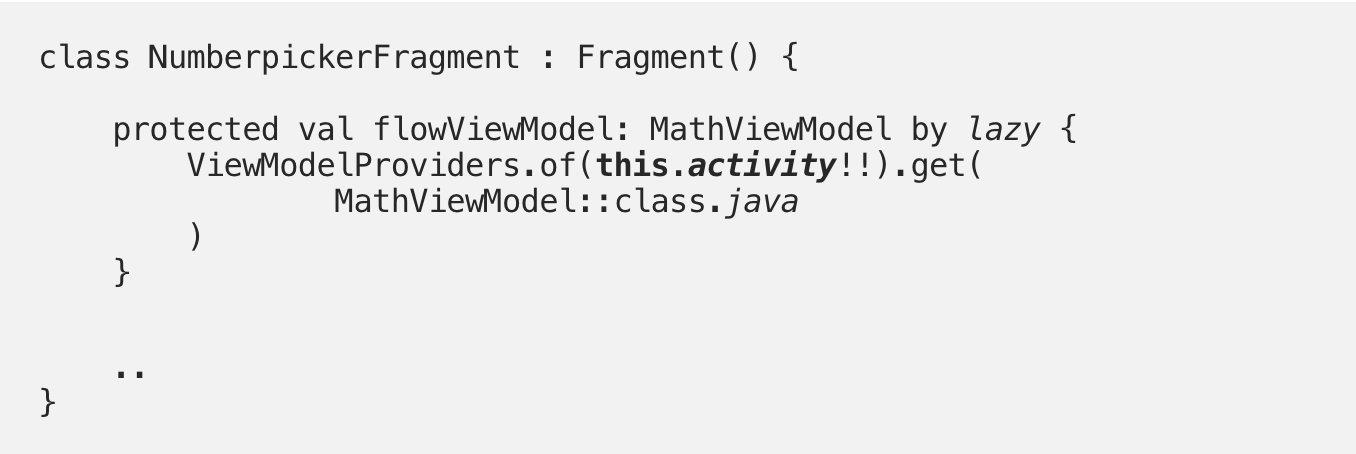

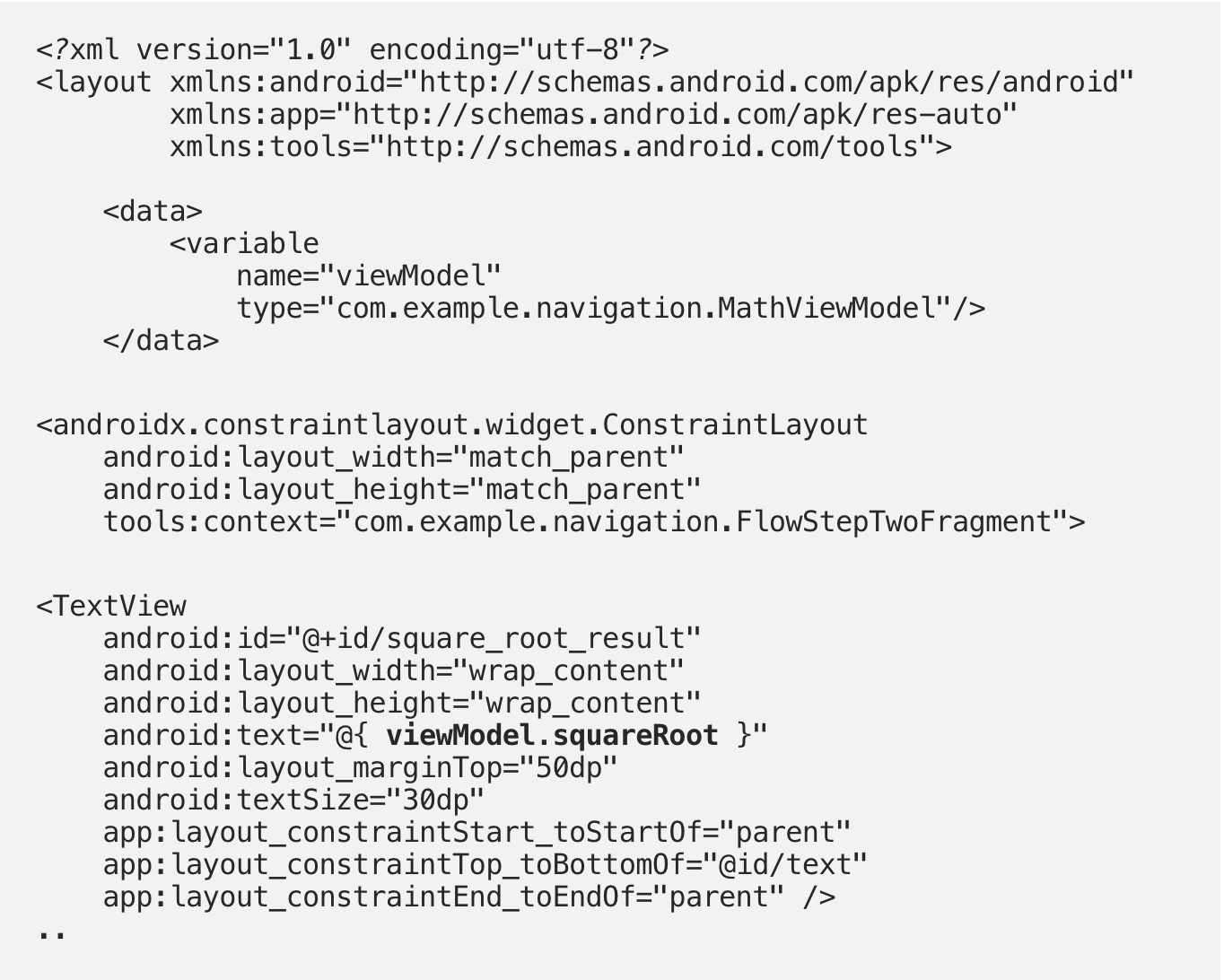

And define a basic fragment for the layout file above. List that fragment in the tablet navigation flow. Next, let the two ‘sub-fragments’ share the same viewmodel with (Mutable)LiveData fields that can be accessed from within both the fragments or their layout files.

Note that the Fragment passes the (single) parent-activity to the ViewModelProviders.of() method to get an instance of the viewmodel. There is an overloaded version of that method which accepts a reference to the Fragment itself, but that method won’t return the viewmodel that is shared across all the relevant fragments of our single navigation activity, so we’re not using that one.

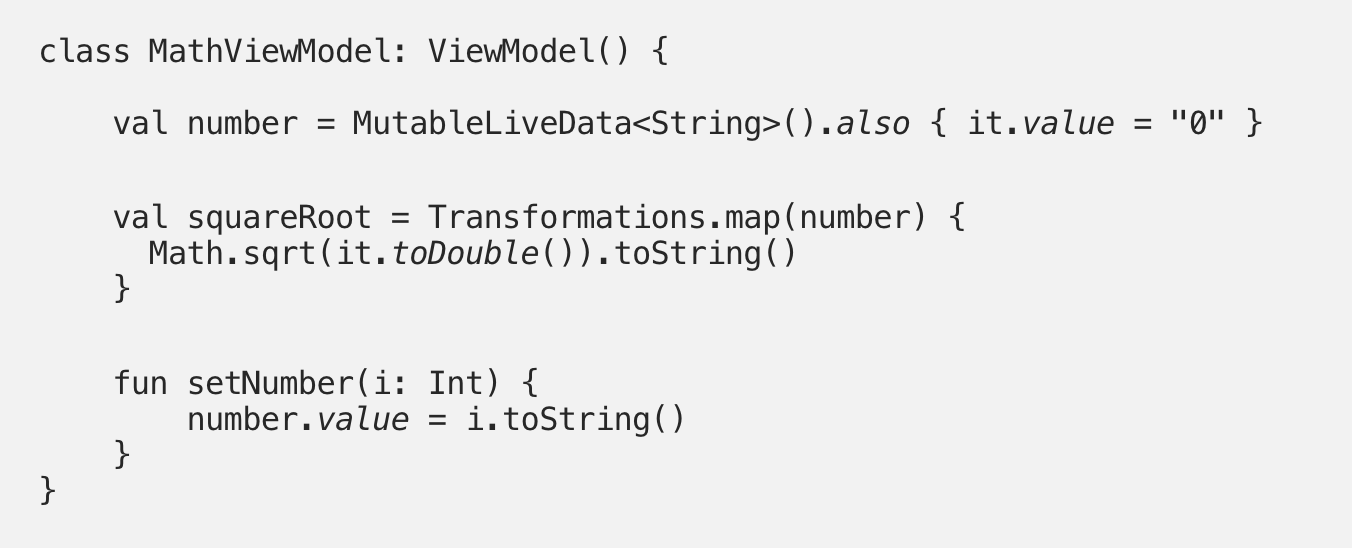

The most simple example of this viewmodel would be something like:

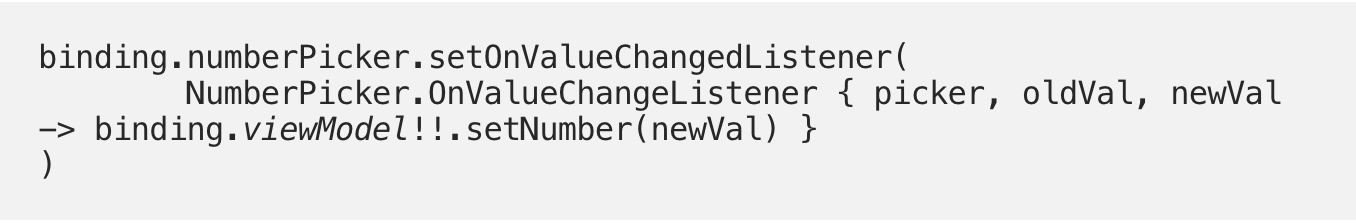

Our first sub-fragment could allow the user to set the viewmodel’s number by, for example, using a numberpicker:

Then the other sub-fragment would immediately respond to the change of the number of that same viewmodel:

For the phone:

In the case of the phone navigation flow, the very same sub-fragments can be addressed in the navigation definition as (non-sub) fragments, and the same viewmodel can be used. Together they form the generic UI elements that are agnostic to the form factor of the device thats hosts them.

Exceptions to this agnostic perfection ;-)

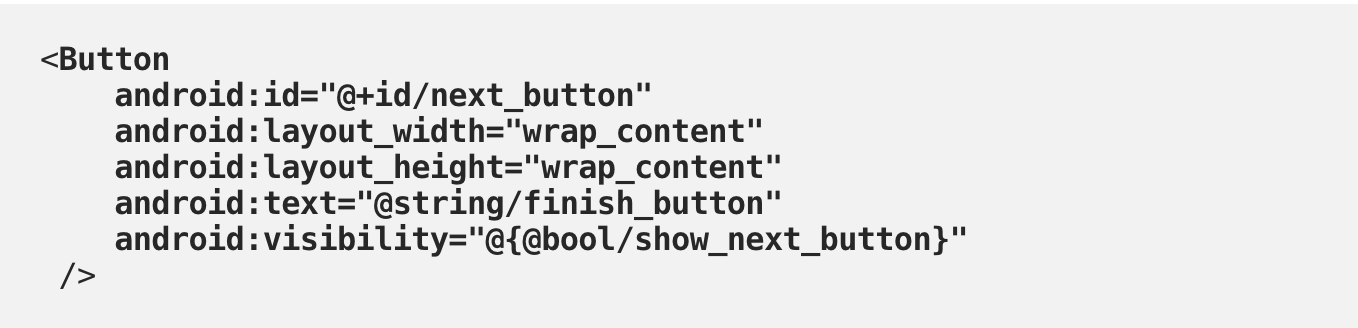

It’s likely that some UI elements should contain views in one form factor and not in another like, for example, a ‘next’ button on the phone, that will transit from fragment A to fragment B, while both these fragments are visible at the same time on the tablet. In cases like these it’s useful to use a boolean resource that has different values on both sides of the breaking point.

Conclusion

Sure, for the simple example App, the word ‘overkill’ is an understatement when choosing this approach, nevertheless when the agnostic (generic) parts of the app get more complicated, then soon there will be a break even point fFrom which onwards this approach has the potential to finally fulfil that long coveted promise of fragments.